At about 10 PM this past Monday, I found myself trying, with little success, to decipher a 1955 study titled Sedimentary Petrology of the Cretaceous Sediments of Northern Delaware in Relation to Paleogeographic Problems. The fact that I chose to engage with this impenetrable text instead of starting to write about this week’s neighborhood speaks volumes about the extent of my procrastination issues.

This wasn’t purely a time wasting exercise though, I have Instagram for that. I was reading about Cretaceous sediments because they were directly responsible for making this week’s neighborhood, Charleston, one of the most important towns in early Staten Island history. In the late 19th century, clay rich Charleston was the heart of the East Coast’s brick-making industry, with its factory employing hundreds of workers and producing nearly 20,000 bricks daily.

Today, this sparsely populated corner of the borough feels far removed from its bustling days as a company town, a place to pass through rather than linger. Much of this transformation traces back to a 1961 zoning amendment that reclassified the neighborhood from residential to manufacturing. Faced with the prospect of industrial plants, diesel-spewing tractor-trailers, and Staten Island’s only correctional facility as neighbors, locals moved out en masse. Eventually, even the prison was abandoned.

None of this is to say it’s not a place worth visiting—because it very much is. It has the city’s borough’s only New York State park, a German beer hall, and even its own haunted house. And it all started around 100 million years ago.

CLAY, GURL

During the Late Cretaceous period, roughly 100 million years ago, rivers and streams carried sand, clay, and other sediments into the shallow coastal seas that covered parts of what is now the Mid-Atlantic. These deposits accumulated in floodplains, swamps, and estuaries. Over time, as sea levels fluctuated and the coastline shifted, they became part of a geological layer known as the Raritan Formation.

In southwestern Staten Island, particularly around present-day Charleston, you can find extensive beds of kaolin—a fine, white, “highly siliceous, micaceous clay,” also known as fire clay. Kaolin, prized for its heat resistance, was essential for making firebricks used in kilns, furnaces, and chimneys.

These clay deposits caught the attention of Bavarian brick baron Balthasar Kreischer.

Kreischer emigrated from Bavaria in 1836, one year after the Great Fire of 1835 had devastated Manhattan, inspired, he said, to “help rebuild the burned city.” He was also undoubtedly inspired by the prospect of making an arschvoll of money.

The fire had triggered a reevaluation of city building codes, making flame-resistant materials like brick the preferred choice for new construction. Sensing an opportunity, Kreischer soon found himself co-owner of a brick factory on the Lower East Side. In 1855, acting on a tip from an employee about the area’s clay beds, he bought a large tract of land in Charleston to open a quarry and a second factory.

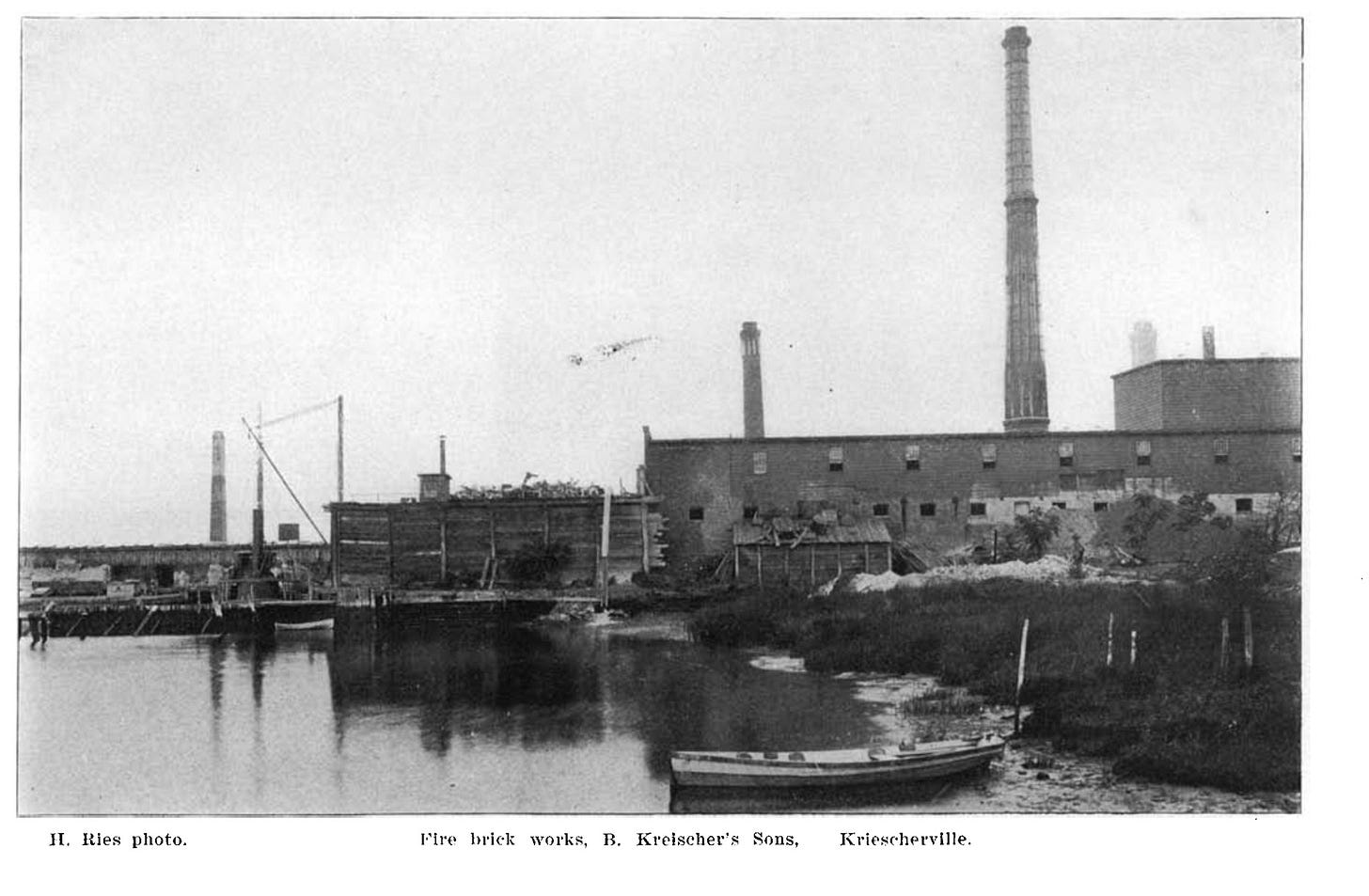

The new factory was strategically situated on the water, allowing bricks made from the local clay to be easily loaded onto boats for delivery along the eastern seaboard.

As the factory expanded, Kreischer needed somewhere to house his hundreds of employees—mostly single German men—who dug the clay and fired it into bricks. He built several buildings for his workers, including a row of detached homes that still stand today.

In addition to houses, the brick tycoon also built a post office, a general store, and a church. As the rural enclave transformed into a factory town, the community recast itself in his image, and the village of Kreischerville was born.

The Androvette family, who had named the area Androvetteville after settling there in 1699, didn't protest the change. They were profiting handsomely from the Kreischer dynasty—building houses, running shipping companies that serviced the factory, and eventually taking over the entire brick operation in 1900. The Androvettes never attempted to restore the town’s original name, but during World War I, anti-German sentiment ultimately led to the area being renamed Charleston.

In addition to housing his workforce, Kreischer built three lavish residences for his family: his own 26-room Italianate mansion, Fairview, and two matching Victorian mansions on Arthur Kill Road for his sons, Charles and Edward. Balthasar died the year after the twin mansions were built.

On June 8, 1894, Edward Kreischer was found dead in a pool of blood underneath a tree somewhere between his house and the factory. Though the death was ruled a suicide, there was widespread speculation that Edward was murdered.

Edward’s former house burned down sometime in the 1930s. Charles’ house remained, and though sparingly occupied, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

MEET JOE BLACK

A ramshackle Victorian mansion perched on a hill, linked to murder and suicide, inevitably acquires a certain reputation.

The number of reported supernatural encounters in the former Kreischer home is only eclipsed by the number of videos on YouTube documenting those encounters. Paragons of journalistic integrity like the New York Post (Haunted, Abandoned, and Hella Creepy) and Inside Edition have done deep dives into the spooky activity at the house. Even America’s most trusted doctor, Dr. Oz, joined in on the fun, enlisting paranormal investigator Anna Raimondi to explore the mansion. She delivered an eerily accurate account of a real crime that had occurred there—claiming she had no prior knowledge of the incident.

The Dr. Oz segment focused on a gruesome crime involving members of the Bonanno crime family, a handful of hacksaws, and a furnace.

In 2005, Gino Galestro, a crew leader in the Bonanno crime family, paid Joseph "Joe Black" Young, who was working as the mansion's caretaker, $8,000 to rub out Robert McKelvey, another Bonanno associate who owed him money. McKelvey was lured to the hilltop mansion where Young, hiding behind a door, jumped out and stabbed the mafioso. After McKelvey managed to break free, Young chased him down and tried to choke him. When that failed to kill him, Young dragged McKelvey to a shallow pool and drowned him.

Young then made a quick trip to a nearby Home Depot for hacksaws, tarps, and duct tape. With the assistance of other Bonanno associates, he chopped the body into small pieces and loaded the parts into the house’s coal-burning furnace.

In March 2009, Young was convicted of murder and other racketeering offenses and sentenced to life in prison.

PASS THE TABU

Late last Tuesday afternoon, I headed back to Charleston with two goals in mind: photograph the Kreischer mansion and maybe find an old Kreischer brick.

I arrived just as the sun was beginning to set. While driving down one of the neighborhood's several dead-end streets, I spotted an opening in a corrugated fence, a sliver of the bay reflecting in the distance. After making sure nobody was around, I ducked through the gap.

I carefully descended a muddy slope, slick from the recently melted snow. When I emerged from the trees, I had an expansive view of the Arthur Kill. The decaying, barnacle-encrusted hulks of several boats lay just offshore, home to flocks of cormorants and gulls that took to the air at my arrival.

The dark sand of the beach was littered with small pebbles, thick, glistening clumps of mussels, and a veritable constellation of old car and boat parts, but no bricks. So I kept walking. In some spots, the shoreline narrowed to just a foot.

I skirted this edge, boots squelching in the soft sand, determined to keep going. Then I found it: a jumble of crusty red and yellow bricks. It didn't take long to find one with the Kreischer imprint, though it was broken—only the “ischer” remained.

Regardless, I was happy with my find. By this point, I had traveled quite a distance from where I had started, so I decided to continue in the same direction hoping to find an exit further down the shore. In retrospect, this was a mistake.

A few yards further, the shoreline virtually disappeared. As I leaped to avoid a pool of stagnant water, my boot landed on a soft patch of sand and began to sink. The slow sucking sound was sickening. After managing to dislodge my boot, I assumed a hunched, quasi-crab-like posture, hoping that with a lower center of gravity and scurrying gait, I might somehow displace my weight enough to make it through this ersatz patch of quicksand. I managed to make it to dry land with both my boots intact, but my prospects were not looking good. With the tide coming in and retreat no longer an option, I pulled myself up on a small ledge and headed inland.

After bushwhacking through a dense thicket of phragmites, I emerged into a semi-open, swampy woodland. The woods were dotted with several mounds resembling the large middens once found all over Staten Island's south shore.

Among them were the remains of several old cars and rusted-out boiler parts. Maybe these castoffs were the middens of the future, the rusted carcasses of Chevy Malibus in place of piles of oyster shells.

Given enough time, these relics could become part of the next geological layer—the Fiero Formation —raw materials for the future barons of Staten Island.

I wandered around the woods for a while, but the dense vegetation and muddy creeks stymied every attempt to find an exit. My phone’s GPS was useless, though it did let me know that I was getting alarmingly close to the Richmond Boro Gun Club shooting range.

I decided to head back to the shore. As I crashed through reedy corridors of indeterminate origin, it occurred to me that this Kreischer brick might be bringing me bad luck.

Visions of Greg Brady face-planting into a coral reef played in my head. I am, of course, referencing the legendary Brady Bunch Season 4 Hawaii trilogy where Bobby finds what he assumes is a good-luck tiki idol at a construction site. Several tarantula sightings, the aforementioned surfing accident, and Alice’s devastating hulu injury proved otherwise.

Maybe I needed to jettison this broken brick, which, frankly, was starting to stink. But if I got rid of it, this whole escapade was for nothing.

I soon found myself near The Tides, a gated waterfront senior community that had been built on the ashes of the old Kreischer factory.

Not wanting to deal with what was sure to be an over zealous security team, I headed back into the woods. A few minutes later, I spied a clearing in the distance that looked to be someone’s backyard. It was filled with lawn ornaments—never a good sign—but I was getting desperate. The sun had set, and my hand holding the malodorous brick was soaked and freezing. It was do or die. Assuming the same hunched crab stance that had served me so well on the beach, I sprinted across the backyard, past a gate, and out onto the street. I'm not sure what would have happened if I'd encountered a passerby in my current condition—hunched and scurrying, pants covered in mud, hair full of chaff, clutching a reeking, mossy brick. Thankfully, it's a very quiet neighborhood.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s field recording begins with the crunch of my footsteps on the snow-covered trails of Clay Pit Ponds Park, on my way to a partially frozen creek. The middle section shifts to some industrial clanging of an indeterminate nature before finishing up at the windswept emptiness of Sharrott’s Shoreline.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

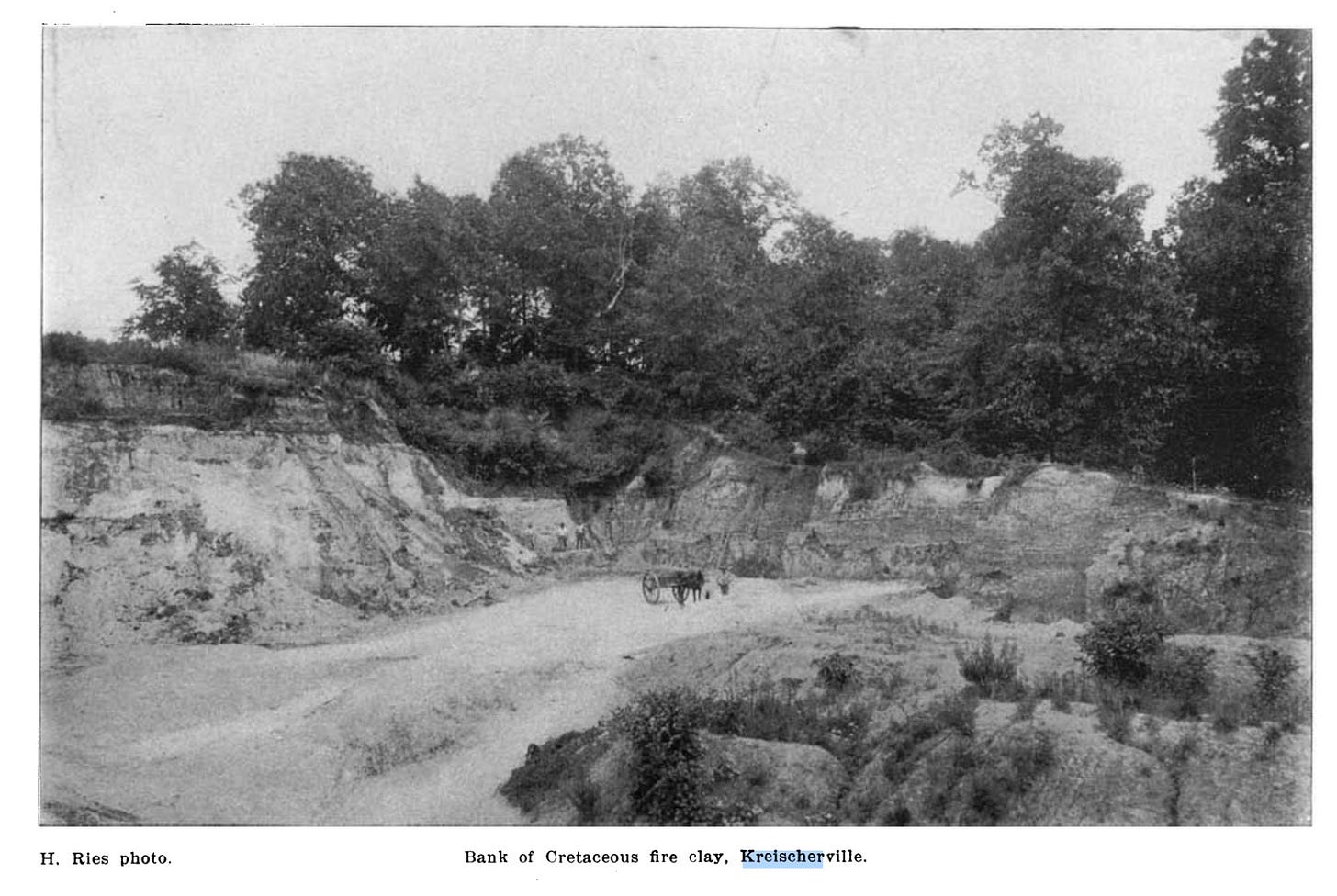

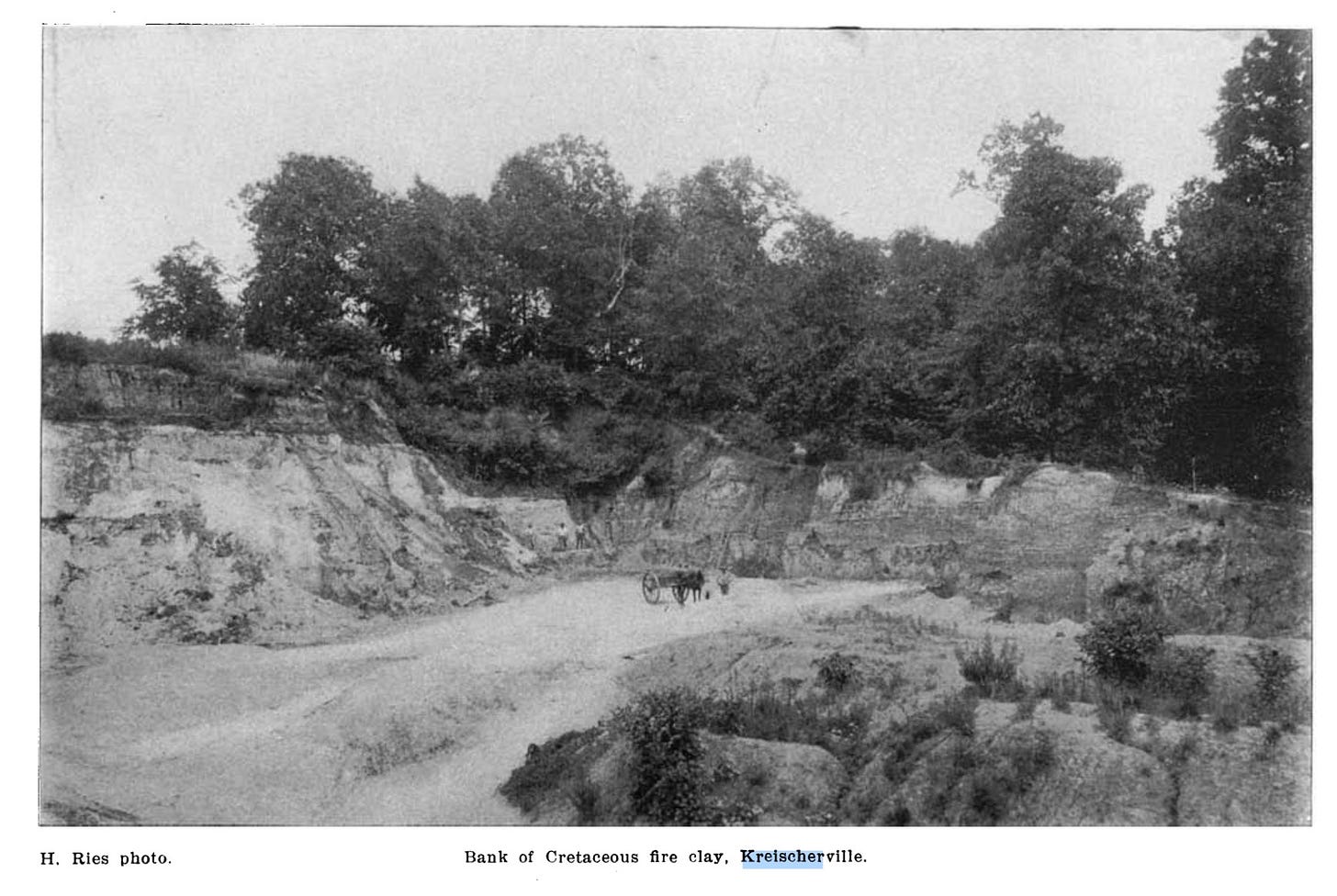

Sticking with today’s theme, this week’s featured photographer is not really a photographer but rather a geologist: Heinrich Ries. I was skimming a copy of his 1900 book Clays of New York: Their Properties and Uses when I came across his photos of various brickwork operations. I love vintage photos that document industrial processes, and Ries’ images included several from the Kreischer brickworks, which I’ve included below.

The Brooklyn-born Ries (April 30, 1871 – April 11, 1951) was the chairman of the geology department at Cornell University and wrote several books on geology. He was also a pretty good photographer. These are all screenshots from his book, so I’ve included the captions.

ODDS AND END

Killmeyer’s Old Bavaria Inn may be the oldest bar and restaurant in Staten Island.

Clay Pit Ponds Park is the only New York State park

within the city's bordersin Staten Island. The park, as the name suggests, covers the land that Balthasar Kreischer once quarried for clay. It is home to over 180 bird species, including Broad-winged Hawks, Black-billed Cuckoos, Olive-sided Flycatchers, Red-eyed Vireos, and Blue-gray Gnatcatchers. A walk in the woods (or horseback ride) followed by a stein and some spätzle may be the perfect Charleston day. You could also grab a sandwich at Artisan Bakers Group, a bakery and sandwich shop in the middle of an industrial park. Maybe skip the beach, though.For obvious reasons, I avoided photographing the Arthur Kill Correctional Facility in Charleston. It wasn’t until this week that I learned the prison—still surrounded by razor wire and once home to serial killer Paul Bateson—is actually a movie studio set owned by Broadway Stages. When the jail shut down in 2011, the production company took it over to provide an authentic prison-like setting for shows like Orange Is the New Black.

.

Thank you for continuing to risk life and limb for our reading pleasure.

Came here for the photos, stuck around for the awesome storytelling! Another awesome post Rob!