Back in the days when mustaches weren’t ironic and people bought records with the intention of listening to them, Brooklyn was viewed as somewhat of a backwater, spoken of derisively, if at all. This passage from Tom Wolfe’s 1935 short story, Only the Dead Know Brooklyn, written in an approximated Brooklyn patois, gives you an idea of how the borough was perceived at the time.

He pulls it out of his pocket, an’ so help me, but he’s got it—he’s tellin’ duh troot—a big map of duh whole goddam place wit all duh different pahts. Mahked out, you know—Canarsie an’ East Noo Yawk an’ Flatbush, Bensenhoist, Sout’ Brooklyn, duh Heights, Bay Ridge, Greenpernt—duh whole goddam layout, he’s got it right deh on duh map.

In the mid-1940s, a cadre of Brooklynites, sick of being the punchline, formed "The Society for the Prevention of Disparaging Remarks About Brooklyn.”

Canarsie, on the southeastern shore of the borough, about as far removed from the city center as you can get, was often the butt of those jokes. The place that even Brooklynites could make fun of. All you had to do was say Canarsie, and people would be rolling in the aisles. It got so bad that locals seeking to distance themselves from the widely mocked moniker tried to have the area’s name changed to Lindport after aviator Charles Lindberg.

Don’t Fence Me In

The name Canarsie most likely comes from the Lenape word meaning fenced land. While the Canarsies were all over Brooklyn, Keskaechqueren, the location of present-day Canarsie, was their main settlement. In 1636, Andries Hudde and Wolfert Gerretse made a “purchase” from the Canarsies of roughly 15,000 acres along the southwestern shore of Jamaica Bay with the provision that the tribe could continue to cultivate select parcels of land that they had fenced in.

The Dutch called the new territory Amersfoort, which English settlers later changed to Flatlands. As was often the case, European conceptions of land ownership differed quite drastically from those of the native population, and by 1670, nearly all the Canarsies had been displaced. The tip of Flatlands became Canarsie, forming a peninsula of sorts, bounded on three sides by water: Jamaica Bay, Fresh Creek, and Paerdegat Basins.

For the next two hundred years, the area was mainly used for agriculture and fishing.

A New York Times account from 1865 makes it sound pretty idyllic.

a village of the most primitive simplicity…The fishermen's boats line the beach, their nets hang on the fences, and wagons loaded with bluefish, eels, crabs, and more come and go as they did when our fathers were boys.

Things began to pick up when the Brooklyn and Rockaway Beach Railroad came to town that same year. Trains made the trip from East New York to Canarsie, where people could catch a ferry to Rockaway. The trains held more people than the ferries, so some enterprising Canarsians began to build hotels to accommodate the overflow.

.

SNORES THAT CAUSED DEATH

Even with the new visitors and hotels, Canarsie remained a quiet place. A perusal of the headlines found that most of the news of the day was maritime-related, with extensive coverage of local boat races and ferry accidents.

Then there was the tragic case of Little Anna Churchill, awoken by the sounds of a stranger who had drunkenly stumbled into her kitchen and passed out. When she saw the snoring stranger prostrate on the kitchen floor, she went into shock and died.

Slightly less macabre is the story of a local temperance leader who “mistakenly” made a batch of extremely alcoholic jelly and, upon realizing his error, dumped it behind his house. When some of his fellow teetotalers dropped by for a chat, they were shocked to witness a backyard bacchanal presided over by an extraordinarily plastered Brahma rooster.

The article goes on to recount the drunken exploits of Brown’s other chickens, including a hen who misidentified a pile of rocks and began to brood on them and another who, after frantically scratching at the cement to try to get to some worms, gave up and fell asleep. We’ve all been there.

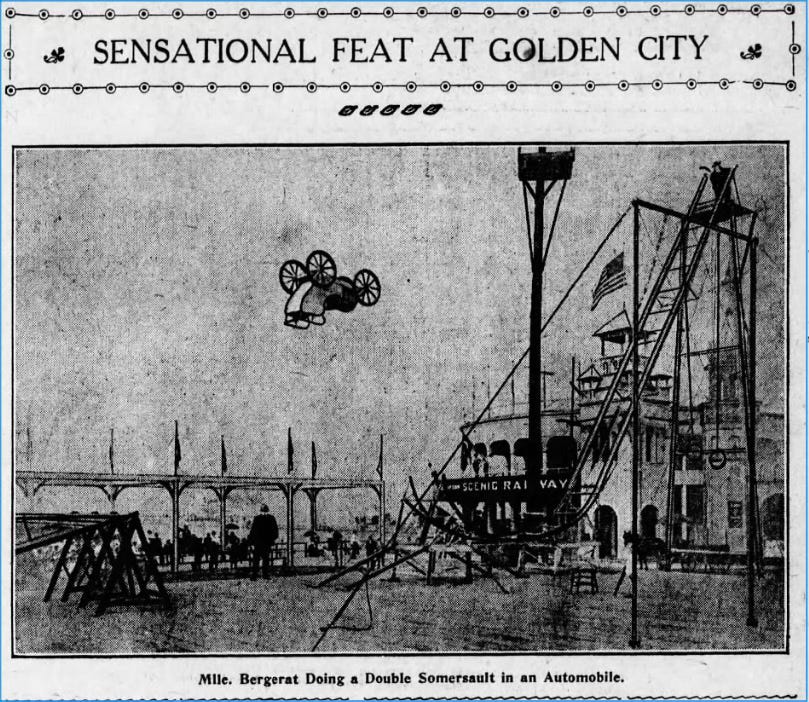

Golden City

While the antics of inebriated chickens are undoubtedly entertaining, they don’t hold a candle to the thrill of watching a horse solve math problems. That’s why when the Golden City Amusement Park opened its door in May of 1907, King Pharaoh, the “educated horse” who could read, write, and do basic arithmetic, was there to draw in the crowds.

Twenty-five thousand people, traveling from all corners of the city, lined up to attend the grand opening of Golden City, Canarsie’s answer to Coney Island.

In addition to King Pharaoh, the park, which cost over a million dollars to build, boasted attractions like the Coliseum Roller Coaster, The Love Journey, and an "electrical-mechanical scenic” production of Robinson Crusoe.

A crowd favorite was the Human Laundry, a ride where thrill seekers and/or clean freaks were “washed” in a giant bath, tumbled for a bit, blown dry with giant fans, then pressed through a system of rollers before finally being ejected down a laundry chute.

Amusement parks, rickety assemblages of wood and plaster, were prone to catching fire, and Golden City was no exception. A 1934 fire proved to be the park’s last act, and any hopes of resurrecting it were quashed when Robert Moses razed Golden City to make way for the Belt Parkway.

After Moses

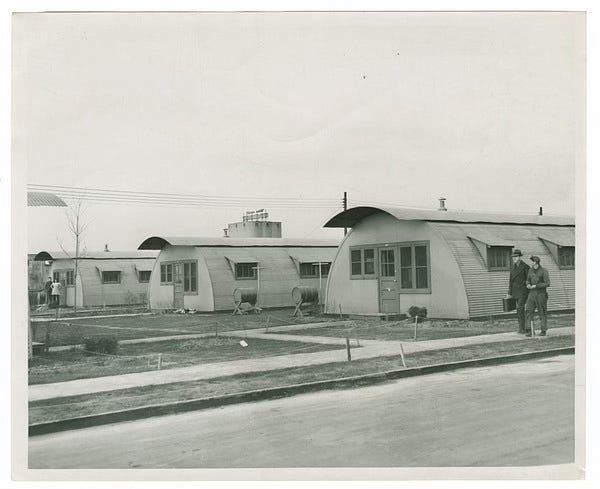

Speaking of Robert Moses, he was partially responsible for the next wave of settlement in Canarsie. I previously wrote about Moses’ idea to use surplus Quonset huts as housing for veterans after WWII in Castle Hill. He did the same in Canarsie and put up 413 huts for returning veterans and their families on the shores of Jamaica Bay.

The huts kicked off the last phase of the neighborhood’s transition from swampland to suburbia. Real estate developers knew there were plenty of people looking to improve their situation, and a new home with a yard and the smell of the sea would be an irresistible draw. The state was generous with loans, and block after block of attached brick houses went up seemingly overnight.

Two big housing projects were also built during this time: The Breuklen Houses and the Bay View Houses, which replaced the Quonset huts in 1954.

Italian American and Jewish families came from neighboring East New York and Brownsville in droves. The neighborhood’s population grew from 30,000 in 1950 to 80,000 by 1970.

At the time, the surrounding neighborhoods—East New York, Brownsville, and East Flatbush—were majority Black, while Canarsie was 98 percent white. Like the generation before them, inhabitants of those other neighborhoods wanted to improve their lot and take advantage of Canarsie's better schools and housing. They were met with resistance.

Integration up North

In his book Canarsie: The Jews and Italians of Brooklyn Against Liberalism, Jonathan Rieder wrote of the growing tension that coincided with the population boom.

Canarsie is a haven, but the gift of immunity is not given freely. To keep their illusion of refuge the residents sealed out alien races, suspicious people, disturbing forces. They made their community into a fortress, a fenced land.

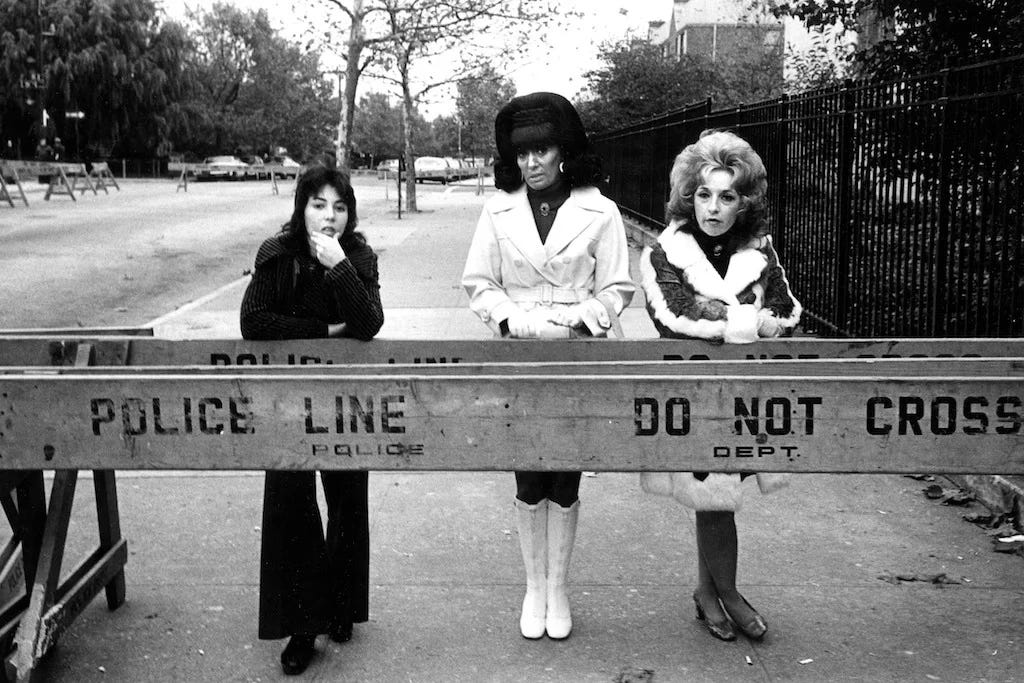

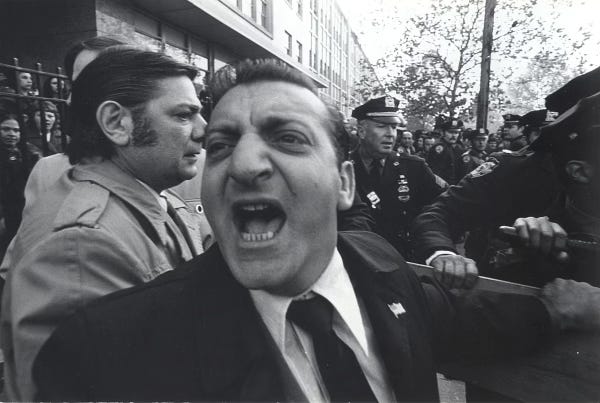

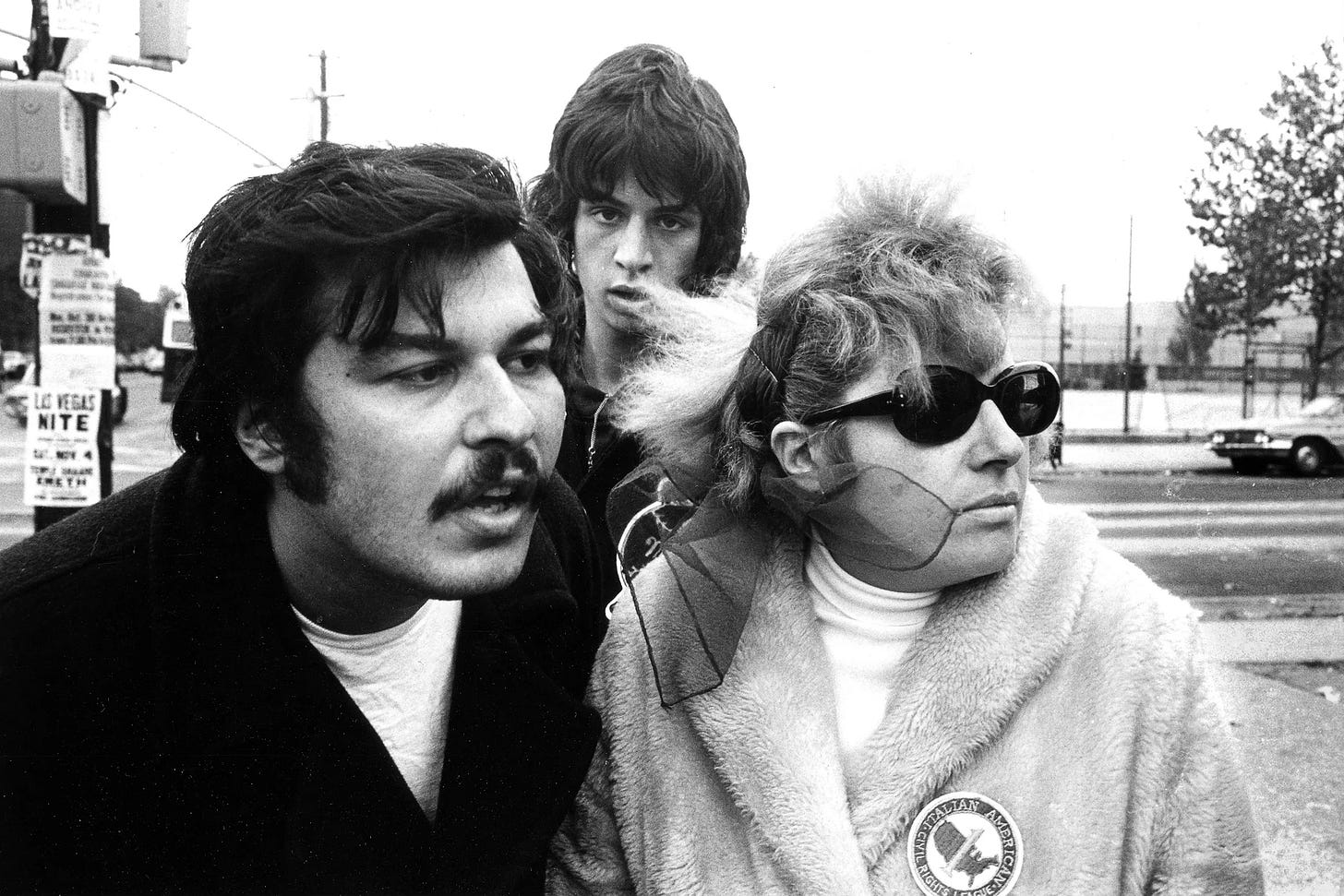

In 1972, 29 Black and Puerto Rican kids from the Tilden Houses in Brownsville were bussed to Canarsie’s John Wilson Junior High School. They were met with 1,500 white protestors. Further protests followed, shutting down several local schools. After months of back and forth, the protestors accepted a Board of Education plan that would keep Brownsville students out of their schools.

Integration up North, an episode from PBS’ Black Journal from the 70s, does a good job of documenting the tension between Canarsie and Brownsville parents.

Also, Ross Barkan wrote a terrific newsletter about Jonathan Rieder’s Canarsie book if you want to learn more.

A 2019 report from NYC.gov states that Canarsie’s current population is 84% African American, with 46% hailing from the West Indies.

PIER

Canarsie Pier was built in 1926 with the idea of turning Jamaica Bay into an industrial port and shipping terminal. Those plans never materialized thanks in large part to Robert Moses, who, for all his flaws, always recognized the importance of public parks. He had Jamaica Bay rezoned as residential and recreational land. Today, the squat 250-yard-long by 300-yard-wide pier, which resembles a floating parking lot, is a popular spot for fishing.

A local advocacy group called The Flossy ( a nickname for Canarsie) is pushing to have ferry service come to the pier. Canarsie is the last stop on the L train, a line plagued with service disruptions. A recent report by The City estimates that only 16% of Canarsie residents can commute downtown within one hour.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s field recording starts off on one of Canarsie’s main drags, Rockaway Parkway, before eavesdropping on a choir practice at the Beth Elohim Seventh-day Adventist church - no, really. The audio ends on the shores of Canarsie Park.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

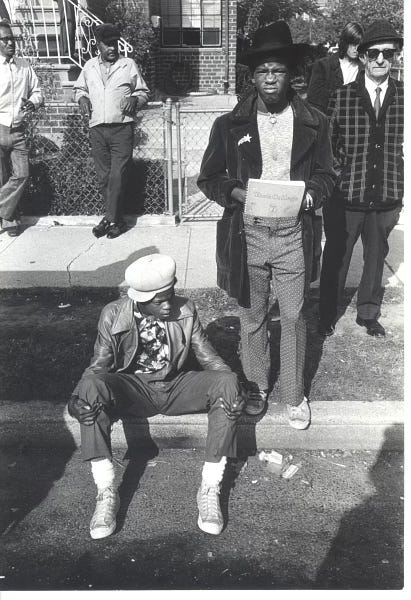

In the 1960s, photographer Sebastian Milito studied photography and film at NYU, The School of Visual Arts, and the New School. After school, he apprenticed in fashion and commercial photography studios in NYC. In 1972, he documented the protests at John Wilson Junior High.

"My passion was photographing street life, the human condition — people doing what they need to do every day to survive and make sense of their lives."

Canarsie school busing protest photographs © Sebastian Milito, courtesy Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History.

ODDS AND END

Right now, at the GC Pawn in Pompano, FL you can find the largest collection of Max Schacknow artworks in the world. Max, who was profiled in a 1989 issue of The New Yorker, was known for his "Black and Whites" - pencil on canvas copies of van Gogh paintings. Though he would show his artwork at art fairs, hanging above them would always be a sign reading, "NONE OF MY PAINTINGS ARE FOR SALE.”

Max grew up in Brownsville but moved to Canarsie. After serving in the war, he started a textile brokerage firm with his brother Harry. When he retired, Max moved to Coral Springs, Florida, and, in 1994, he donated 1.5 million dollars to found the Schacknow Museum of Fine Art. A few years later, after a dispute with management, he pulled his money and art out of the project and opened up a new Schacknow Museum of Fine Art in Plantation, Florida. The original SMOFA houses The Coral Spring Museum. He died in 2013.

Spread Love Eat on Flatlands Avenue is a good option for vegan visitors to Canarsie. You know who you are.

If you are looking for a barrel of pickles, a case of cassava, or a new jade plant, the Brooklyn Terminal Market is your place. When the Wallabout Market was shut in 1941 so the Navy Yard could expand to support the war effort, the less fanciful Canarsie market took its place. The market is a mecca for local vintners who buy grenache and muscat grapes by the crateful.

Clearly, civilization peaked with “Human Laundry.”

Thanks again, Rob, for your photos and research! Growing up, I always found Canarsie to be a strange mix - fishing at the pier, visiting some friends at the housing projects, going by the Terminal Market (a much less intimidating neighborhood than Hunts Point!). I always found the Pier to be a nice rest stop along the Belt Parkway, for watching the water.