Bellerose lies about as far east as you can get while still staying within New York City limits. The neighborhood sits right on the border between Queens and Nassau County—a dividing line that feels especially arbitrary once you realize there’s also a neighborhood called Bellerose on the other side.

The border runs straight down the middle of Jericho Turnpike, a rather nondescript commercial strip with a sign declaring: “Two Counties, One Town.” This whole Queens/Long Island border is full of these sibling neighborhoods. Besides the Belleroses, there are two Floral Parks, a Meadowmere and a Meadowmere Park, and a Belmont in Queens and an Elmont in Long Island, which gets points for trying to differentiate itself by subtraction.

To make matters even more confusing, there are actually three Belleroses: the original Bellerose, founded in 1906 and sometimes known as Bellerose Village, the slightly newer and more modest Bellerose Terrace, added a few years later, and finally, the subject of today’s newsletter, Bellerose Queens—sometimes aspirationally referred to as Bellerose Manor. In practice, most people refer to all three simply as Bellerose.

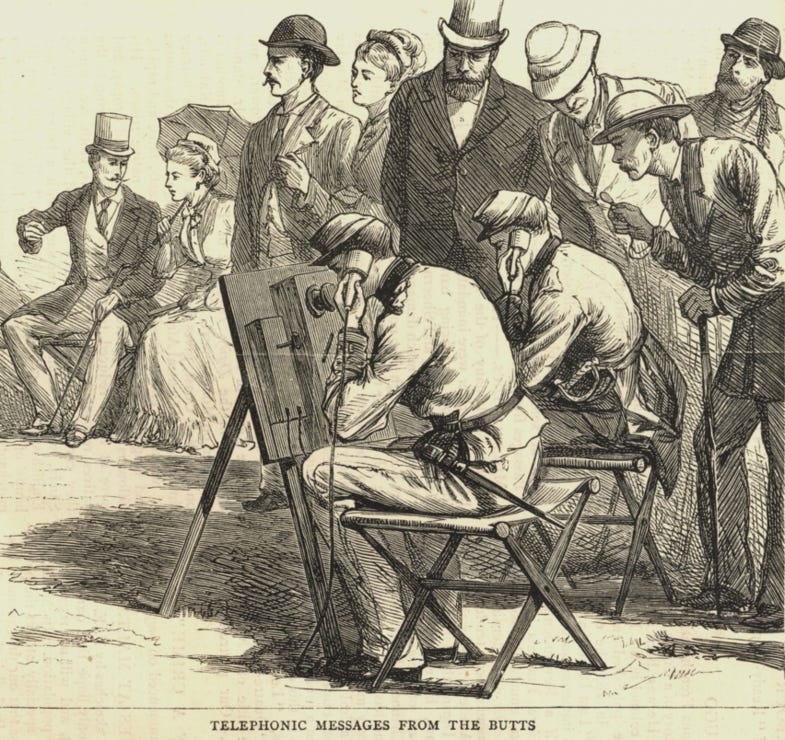

TELEPHONIC MESSAGES FROM THE BUTTS

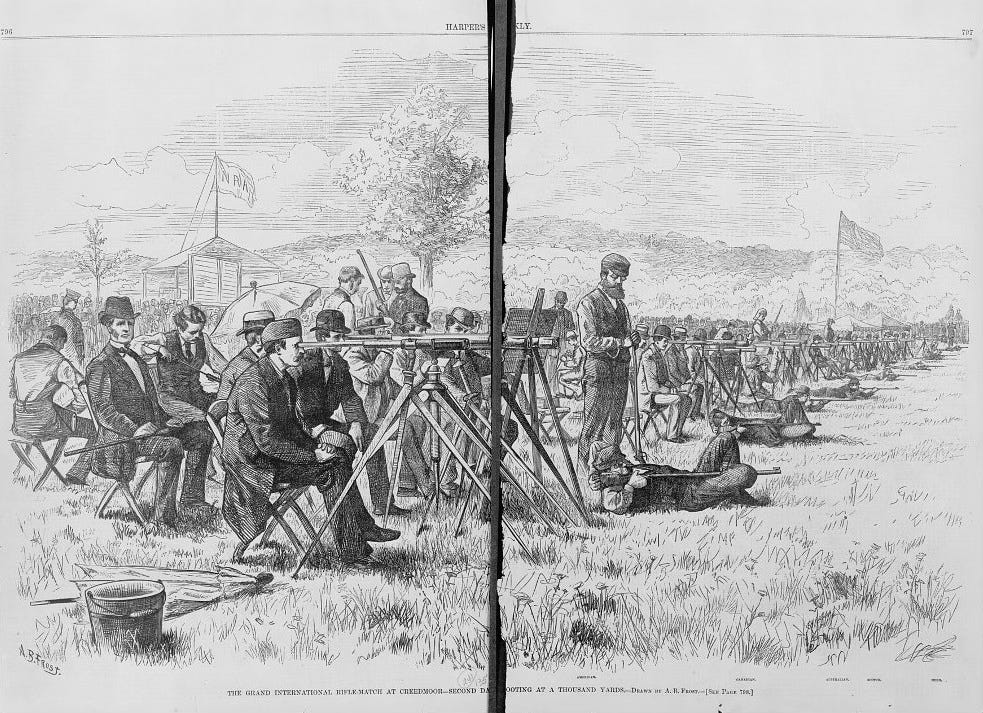

In 1871, the Central Railroad of Long Island purchased a large parcel of mostly empty land on the north side of Braddock Avenue, which included the Creed family farm. They sold part of it to the newly formed National Rifle Association for use as a rifle range and training ground for the New York National Guard. The NRA named the site Creedmoor after its former owners and its low, grassy, moor-like terrain.

Soon after, the Irish Dublin Shooting Club, champion European sharpshooters, sent a notice to the New York Herald challenging American shooters to a long-range contest. The Amateur Rifle Club of New York City accepted the challenge, and a year later, in front of a crowd of over 5,000 spectators, the upstart Americans pulled off a stunning upset.

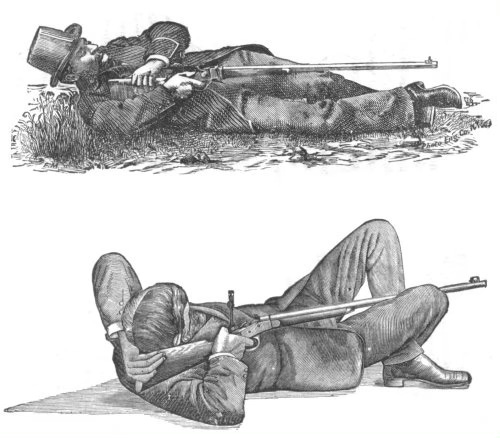

Part of their success was attributed to what is known as the Creedmoor position, a relaxed supine pose that would seem to lend itself more to shooting off, or at least severely burning, a testicle, rather than hitting a bullseye at 1000 yards away, but it worked.

.

By 1907, as the surrounding area became more populated and public interest in watching men lie down and shoot at things waned, the range had shut down.

Today, only a few street names - Range, Musket, and Winchester - serve as reminders of the area’s history.

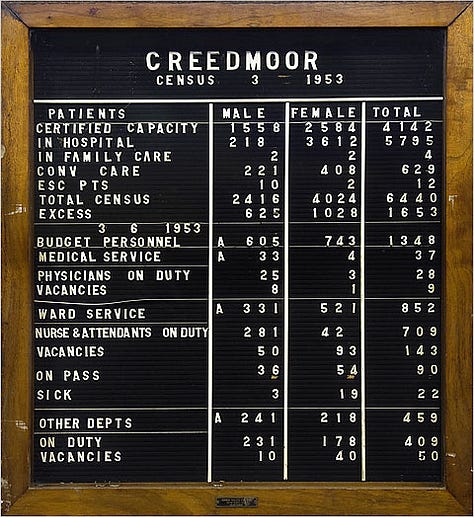

CREEDMOOR

In 1912, the Lunacy Commission of New York State opened a farm colony for the Brooklyn State Hospital on the former rifle range. Like the New York Farm Colony on Staten Island, the hospital sent its first 32 patients to the countryside where fresh air and structured agricultural work were considered therapeutic remedies for mental illness.

In the 1930s, during a nationwide expansion of psychiatric institutions, the facility grew to 70 buildings across 300 acres.

By 1956, the complex, now known as Creedmoor State Hospital, was severely overcrowded, housing 6,018 patients in a facility certified for only 4,188. A year later, the towering 17-story Building 40 opened. Creedmoor’s most recognizable landmark is a near-exact replica of the Manhattan Psychiatric Center on Randall’s Island.

Treatment at Creedmoor ranged from straitjackets and hydrotherapy to electroshock therapy and lobotomies.

Jazz pianist Bud Powell, suffering from migraines after a brutal police beating, spent nearly a year at Creedmoor receiving electroshock therapy. It didn’t work. He returned to the facility several times over the course of his short life.

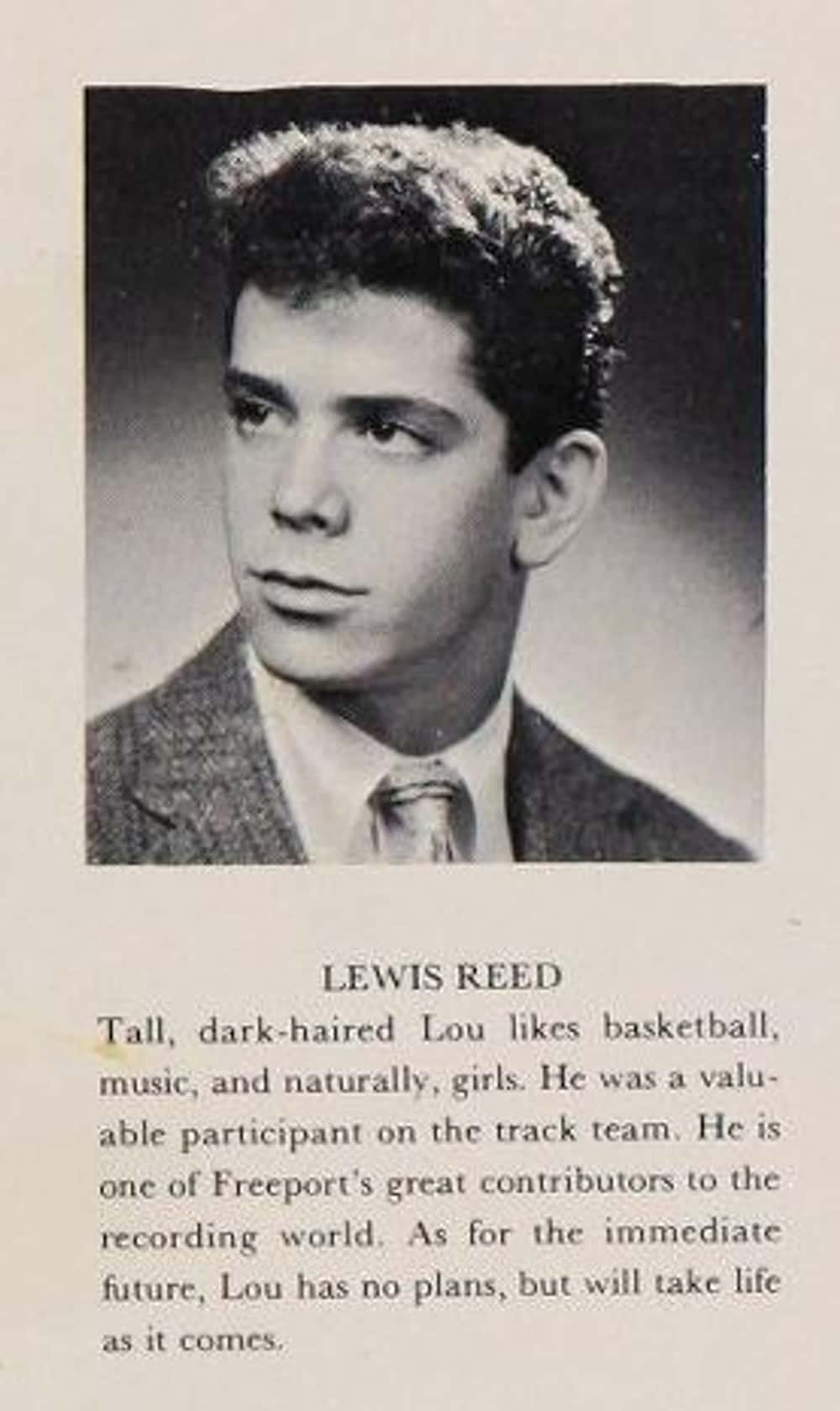

In 1959, at the urging of his parents, Lou Reed underwent 24 electroconvulsive sessions at Creedmoor.

The doctor paced back to the machine, then the two trembling orderlies, barely out of high school and only a year older than Lou was, laid across his chest and knees to brace him for the shock to come. He had read Frankenstein;now he was living it. The doctor flipped the switch on the metal box, the size of a small amplifier, and Lou Reed, who had up to that moment in his life been an acoustic being, became quite literally electrified.

From Dirty Blvd: The Life and Music of Lou Reed - Aidan Levy

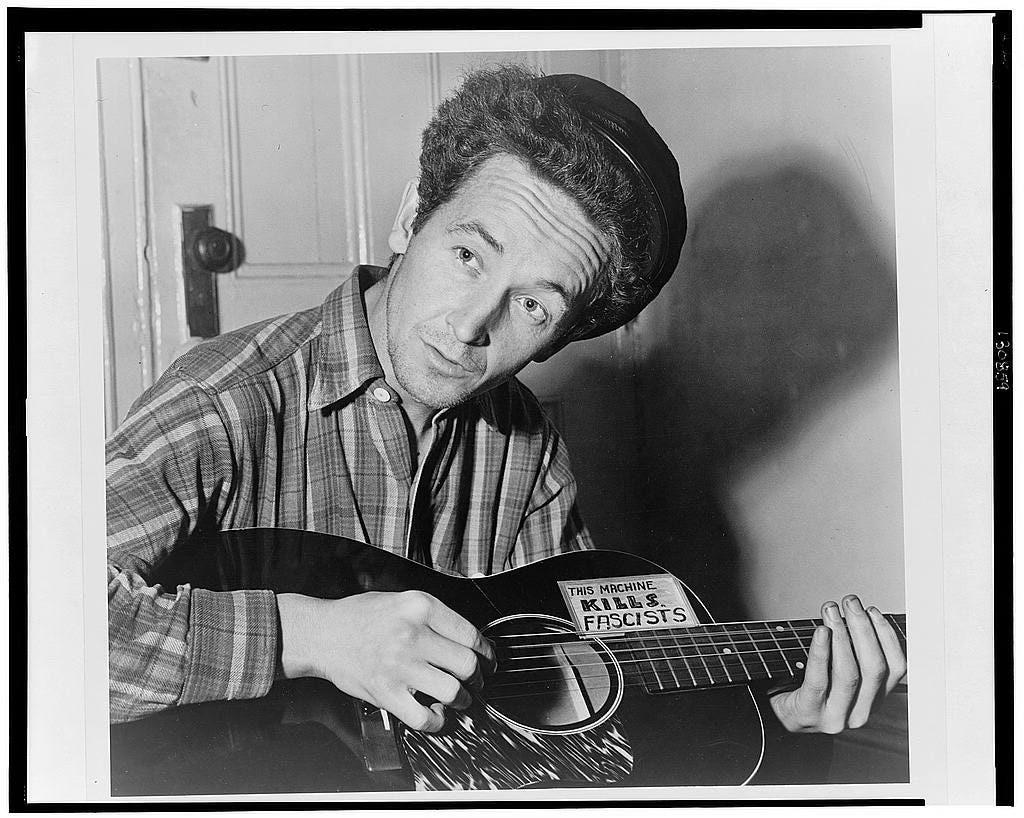

And in 1966, Woody Guthrie—suffering from Huntington’s disease—was transferred here for the final year of his life.

As antipsychotics like Thorazine became more widely adopted and public attitudes toward psychiatric institutions shifted, large hospitals like Creedmoor fell out of favor. Today, Creedmoor operates primarily as an outpatient facility, with only a few hundred full-time patients.

THE LIVING MUSEUM

The high number of writers, musicians, and visual artists who have spent time in mental institutions like Creedmoor might suggest a link between mental instability and creativity, an idea fully endorsed by Creedmoor psychologist Dr. János Marton:

“Extreme creativity and mental illness overlap. And if you are not mentally ill and you are creating great art, you are most likely using drugs or alcohol. You are cheating.

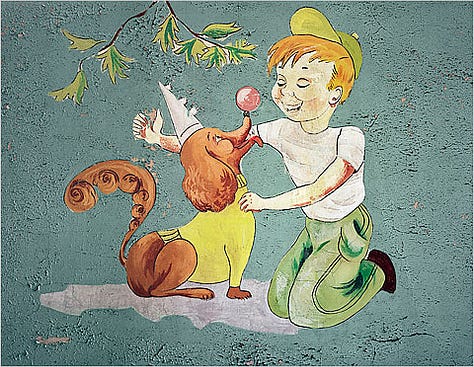

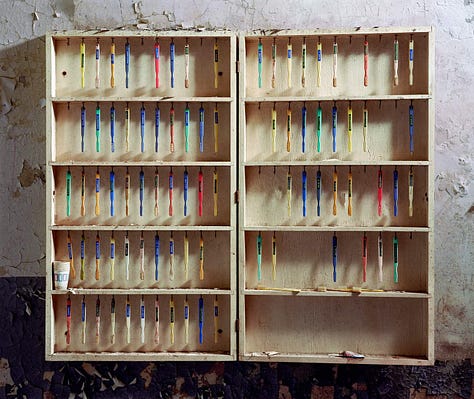

In 1983, Marton and artist Bolek Greczynski turned a dilapidated 40,000-square-foot former dining hall into the Living Museum, the first working studio and gallery dedicated to art made by psychiatric patients. Today, it holds the largest collection of outsider art in the country.

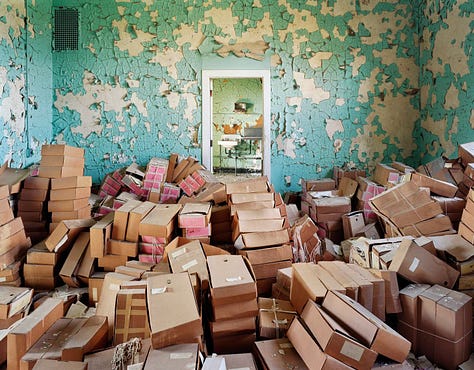

Earlier this week, my GPS led me to a side entrance of the Creedmor campus, a rare break in the relentless 10-foot iron fence that surrounds the facility. Despite an intimidating number of “No Trespassing Government Property” signs, there was no security guard monitoring the entrance. I drove past several abandoned and boarded-up buildings and a few lone individuals wandering the grounds of the desolate campus on my way to the parking lot of building 75.

After I made my way up the stairs and through the doors, I found myself in a vast open space where practically every square inch was devoted to creative expression. Old palettes encrusted with layers of dried paint, soup cans full of Sharpies, multi-colored skeins of yarn, stacks of metal hangers, piles of pastels and pipe cleaners, and towers of spray-painted CRT screens—a collision of color and materials crammed into every corner and corridor of the immense sunlit space.

At the center of the main room, what was once the kitchen, a massive shiny ventilation hood hovers 10 feet off the ground, like a ’60s spaceship, all curves and chrome, festooned with flags and multi colored canvases.

A yarn-wrapped tree branch sprouts from the top of the ventilation hood, and a small bunker-like room built from cinderblocks is tucked away inside it. The room was filled with stacks of LPs ranging from Tchaikovsky to Joni Mitchell and, probably, some Bud Powell and Lou Reed too. A turntable in the back of the bunker is connected to giant speakers that fill the outside room with the sounds of whatever someone put on last. On the day I visited, it was Blondie.

I was lucky enough to be given an impromptu tour by Tim (bassist for the Living Museum house band, the DSM5), who also tends the plant room on the second floor, a lush, verdant work of art in itself.

Tim showed me wire sculptures by John Tursi (his former roommate), Frank Boccio’s intricate dot paintings, and the precise graffiti lettering of James Kusel, who apparently makes a mean Kung Pao chicken. Tim also showed me the studios of Issa Ibrahim and Stephen Spagnoli and introduced me to Paula Brooks, who goes by Sweetpea.

It is a remarkable place, and I think it may be the city’s greatest museum, or at least its most alive.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio features sounds captured before, during and after a 5-mile race in Alley Pond Park and a snippet of audio from inside the Living Museum, with the sounds of Melanie’s 1971 hit Ring the Living Bell blasting on the stereo system juxtaposed against someone playing piano in the musuem’s band room.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

I’ve already featured Christopher Payne’s photographs of the Steinway factory in my Astoria newsletter. His name came up again while I was researching Creedmoor. Chris spent six years documenting former asylums across the country and has a whole book on them.

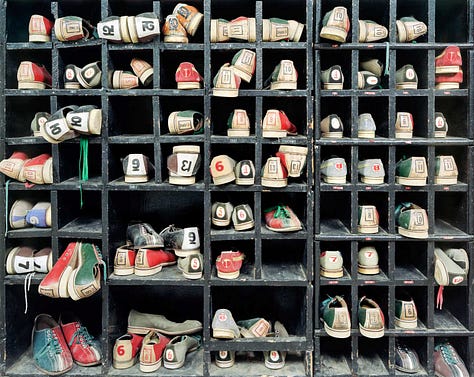

From 2002 to 2008, I visited seventy institutions in thirty states, photographing palatial exteriors designed by famous architects and crumbling interiors that appeared as if the occupants had just left. I also documented how the hospitals functioned as self-contained cities, where almost everything of necessity was produced on site: food, water, power, and even clothing and shoes. Since many of these places have been demolished, the photographs serves as their final, official record.

The first three photos here are from Creedmoor.

You can see more of Chris’s fantastic work on his website and order the book here.

ODDS AND END

Beginning next Wednesday, 3Walls will be showing work from my Neighborhoods project at the Future Fair in Chelsea. You can find them at booth F5. The fair runs from May 7–10.

Here’s the link with more info: https://www.3wallsnyc.com/events-1

Hope to see you there!

In 1925, the United News ran a story titled “Beer Not ‘Near,’ Town All Upset” about a raucous “Beefsteak Stag” party thrown by the Bellerose Fire Department at the Women’s Club during the height of Prohibition. The attendees, it seems, had a rather loose interpretation of temperance laws.

When one fireman stood to lead the band in song, he narrowly avoided a steak “sailing through the air and striking a pretty pastoral painting on the wall with a squishy sound, leaving a gravy stain as big as a two-inch porterhouse.”

Patrolman Murphy, the town’s only police officer, arrived moments later with his dog Sheik—“a combination Beagle and Airedale, with a trace of Holstein cow”—but wasn’t so lucky. A second projectile steak hit him square in the nose, which “altered it from aquiline to retroussé.” Sheik was too busy eating the evidence to assist.

The whole article is worth a read. Even more interesting than the article is the biography of its author, Westbrook Pegler, who was just beginning what would become a notorious career. Pegler began as a sports reporter but would go on to become, for a time, “the most influential and widely read journalist in the country.”

In 1941, he won the Pulitzer Prize for exposing labor racketeering in Hollywood unions. That same year, he came in third, behind Franklin Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin, for Time’s “Man of the Year.” Pegler, who coined the term “bleeding heart liberal,” and has been described as a “soul-sick, mud-wallowing gutter scum columnist,” became a prototype for the modern right-wing populist: the Rush Limbaugh of his day, but with a much better vocabulary.

This 2009 New York Times article documents the last days of the iconic Frozen Cup ice cream stand—a local institution whose closure symbolized Bellerose’s gradual transformation. Once described as a “mostly white enclave of families of Irish, Italian, and German stock,” the neighborhood now has a significant South Asian population, including many Sikhs who worship at the Gurdwara Sant Sagar temple on Braddock Avenue.

Susan Sheehan’s book “Is There No Place on Earth for Me?” recounts the life of Sylvia Frumkin, a patient at Creedmoor diagnosed with schizophrenia. The book was originally published as a four-part series in The New Yorker.

In November 1974, Donna DeMasi, 16, and Joanne Lomino, 18, were both shot on the front porch of Lomino’s Bellerose home by David Berkowitz, aka the Son of Sam. DeMasi recovered, but Lomino was paralyzed from the waist down.

On Monday, June 17, 1940, two B-18 bombers on a training mission from Nassau County’s Mitchel Field collided mid-air over Bellerose, killing all 11 aboard and a woman inside one of the houses below.

While not technically in Bellerose, I had a fantastic dosa right down the road at Hillside Dosa Hutt, a great place to eat after a visit to the Living Museum.

Another great read, Rob!

My wife and I lived in Bellerose in the early 1980s, in the Glen Oaks apartments (now condos), in the shadow of Creedmor. I remember the Frozen Cup well.

In those days, the parking lot at Alley Pond Park was the place to purchase LSD … or so I’m told 😊

These days, I’d rather have a dosa.

I got so excited seeing this subject in my inbox- Bellerose has been my home my whole life and most New Yorkers have never heard of it! Thanks for highlighting all the interesting art + history.